I’d lost count of the number of steps going

up, or for that matter, those going down. All

I knew was that the

trail was never flat,

and that frustratingly

our destination always seemed just over the next hill – but for the most part, never was!

I was in the middle of the fabled “Mountains of the Moon”; not well known but with a long history. Aristotle in 350 BC first

referred to the origin of the Nile in the Silver Mountain – the earliest known reference to the Rwenzori. It was then Ptolemy in AD150 who talked about “Mountains of the Moon whose snows feed the lakes, sources of the Nile”. Interestingly, both Aristotle and Ptolemy referred to a single mountain whereas the Rwenzori is a distinct isolated mountain mass along the Ugandan and Democratic Republic of the Congo border, comprising six individual mountains, each with multiple peaks.

In 1906 the Duke of the Abruzzi made his successful exploration of the snows of the Rwenzori, climbing and mapping the six snow mountains and making the ascent of most of the snow peaks, of which only one had previously been climbed. The last known successful climb of all six mountains was a Polish team in 1975, where over a four-week period they achieved the first complete traverse of the main ridge of the Rwenzori mountains – Gessi, Emin, Speke, Stanley, Baker and Luigi di Savoia.

The Duke’s expedition had reached the snows by the valley of the Mubuku river, which flows eastwards from the glaciers. In more recent times many parties, including the Polish expedition, use what’s referred to as the Central Circuit, using the Bujuku route that progresses anti-clockwise.

My objective was to climb all six Rwenzori mountains, and as many of the peaks as possible, using another relatively new route that starts in Kilembe and takes a north/south approach (but had no trail to the northern two mountains!). If successful, I would be the first person to do so in more than 45 years and the first using the Kilembe route. The Rwenzori are challenging. It rains 10 months of the year (gumboots are compulsory); lacks the mature infrastructure of Kilimanjaro and Mt Kenya; has limited local knowledge of Mounts Gessi and Emin; and involves constantly trekking up and down in mud and slush. Thankfully African Ascents and Rwenzori Trekking Services provided all the logistics and guidance and made sure things went very smoothly.

Leaving Kilembe, the first three days are a constant up and down grind (albeit in some beautiful scenery) to get to the top of the Rwenzori plateau. It’s constantly ascending but not a gradual climb, it’s more like 2 steps up and then 1 step down. After three days my support party and I arrived at Bigata camp (4059m) from where people leave to climb Mt Barker (4843m) or continue on for Mt Stanley (5109m). I hadn’t fully acclimatised so Day 4 ended up being a rest day (after more than a nett 2500m ascent in three days), when I sat reading and watching it rain!

I decided to head straight to the next camp via Barmwanjara pass (4450m) and leave Mt Barker for the way out. So I headed to Butawa camp (4006 m) and then set out at 23.00. The weather was pretty good for the Rwenzori but still the going was slippery and slow, making it

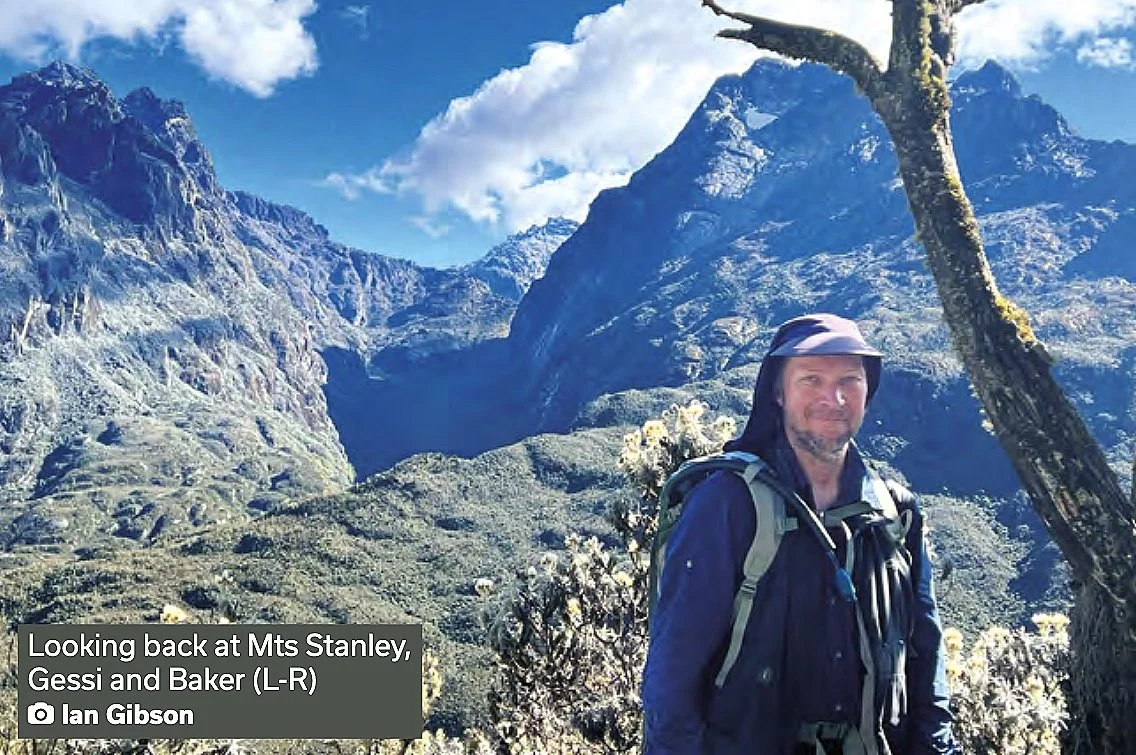

a 17 hour round trip – but not without bagging the 3rd highest mountain in Africa, Margerita peak on Mt Stanley (5109m).Given the slow pace, I decided not to try the other peaks and so headed back.

Next day we left the last of the huts and trekked to a site at the base of Mt Speke. Time was becoming an issue, so I decided to go around Mt Speke and head straight for Mts Gessi and Emin – the two northern mountains that no one goes to and had never been climbed via the Kilembe route. There were no trails once we left the base of Mt Speke so it was a case of finding a route and cutting our way through using a panga. Fortunately for me, I had assistance to clear a path. That night we camped at a new site, subsequently named Camp Gibson, that had great views of the south face of Mt Emin.

Next day, after more trail finding and cutting, we arrived at Roccati Pass Rock camp shelter (4130m) which sits between Mts Gessi and Emin. The following day we successfully summited Iolanda peak (4715m) on Mt Gessi making me the first person to do so using the Kilembe route; the first person over 60; and probably the first Australian to do so. A great day! Tomorrow it was Mt Emin’s turn. Mt Emin is very different to Mt Gessi. Whereas yesterday there was an obvious line

to take, today was more “try and see” leading to some false starts. Mt Emin is also scree and loose rocks, so with only 200m to go I sadly decided the risk from falling rocks had become too great. I turned back and left Mt Emin for another day.

I was conscious that we still had another three mountains to climb (Speke, Baker and Luigi di Savoia), but that’s where the weather decided to have a say and coated the whole area in snow. Time was now definitely against me and it was becoming an issue if I was going to make the exit date. Snow and time meant I passed Mts Speke and Baker but still managed to climb Weissmanna peak (4619m) on Mt Luigi di Savoia on the way out. The exit from Bigata camp (4059m) was meant to take 3-4 days including climbing Weissmanna peak but I’d only left two days!

While I’d attempted only four of the six Rwenzori mountains, I’d climbed Mt Gessi and gone where few people have ever been. Now I know the place, how things work, and what a successful attempt needs – apart from some luck with the weather! I was enthused enough with Ugandan climbing to want to return to the Rwenzori. Next time, however, I’d add traversing some of the nearby volcanos and climbing Mt Kenya to achieve the African Triple Crown (Kilimanjaro, Mt Kenya and Mt Stanley).

After leaving the Rwenzori I met up with my family and went on safari for 5 weeks across Uganda, Kenya and Zimbabwe... but that’s another story.